|

|

One of the members of SAGE (UK advisory panel on CV) speaks to the Guardian.

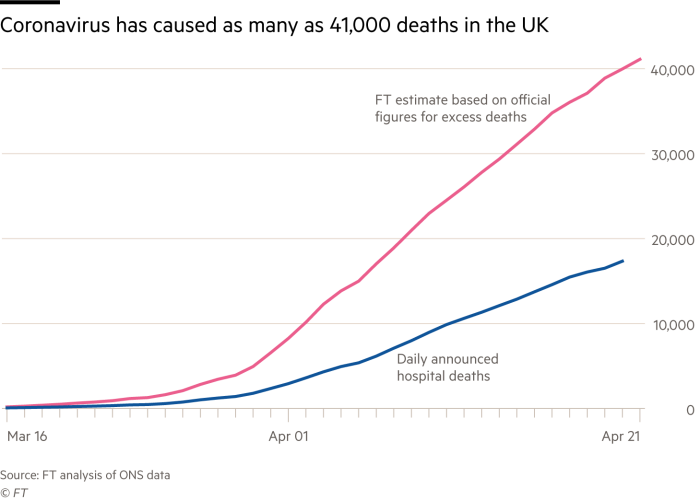

tl;dr - gov't was warned repeatedly about what was coming by their advisors, and failed to take action in time. Boris like "rabbit caught in headlights." Now gov't is trying to pass the buck by claiming they were "guided by science."

https://www.theguardian.com/world/20...navirus-crisis

The first official report of somebody dying in hospital having tested positive for Covid-19 caught in the UK came on 5 March. Still, elderly and vulnerable people were not given any advice to shield themselves. A member of one Sage advisory committee said that around this time there was a gap between the scientific advice and political messaging. “The prime minister was going around shaking people’s hands to demonstrate that there wasn’t a problem. There was a disconnect at that point. We were all slightly incredulous that that was happening.”

Given the repeated denials, it can be overlooked that the reason the world believes that attaining herd immunity was the government’s approach is largely because Vallance said it was.

Asked on Sky News what proportion of the population would need to become infected to achieve herd immunity, Vallance replied: “Probably about 60% or so.”

At a press conference the following day, Johnson famously said: “I must level with the British public: many more families are going to lose loved ones before their time.”

Whitty announced then that the initial effort to contain the disease by testing and tracing had been abandoned, yet despite that, and Johnson’s dire warning, the measures discussed for the new “delay” phase were almost negligible. People over 70 were advised not to go on cruises. Johnson said even “household quarantine” would not be required until sometime “in the next few weeks”. The government’s published plan did say that social distancing and school closures could be considered.

Vallance made his media appearances the following day, explaining the herd immunity approach. He was asked on Sky News why in the UK “society was continuing as normal”, and it was put to him that a 60% infection rate would mean “an awful lot of people dying”. Vallance replied that it was difficult to estimate the number of deaths, but said: “Well of course we do face the prospect, as the prime minister said yesterday, of an increasing number of people dying.”

Matt Hancock, the health secretary, issued the first denial that herd immunity was part of the government’s plan, despite Halpern and Vallance having days earlier indicated that it was, in a column in the Sunday Telegraph on 15 March. “We have a plan, based on the expertise of world-leading scientists,” Hancock wrote. “Herd immunity is not a part of it. That is a scientific concept, not a goal or a strategy.”

Ferguson held a press conference on 16 March to explain the new findings. His colleague, Prof Azra Ghani, said: “Under strategies we were pursuing, we were expecting a degree of herd immunity to build up. If we now realise it’s not possible to cope with that in the current health system, and it may not be acceptable in terms of the numbers, then we need to try and reduce transmission.”

The Guardian asked Ferguson how that policy could be contemplated, if it predicted that 250,000 people would die. He emphasised that he was never sanguine about people dying, and made it very clear that it was the politicians, not the scientists, who decided on policies to pursue. “While policy can be guided by scientific advice, that does not mean scientific advisers determine policy,” he said.

Prof Graham Medley, another Sage member, and chair of its influential modelling subcommittee, agreed that while the scientists gave their analysis on the epidemic to inform the politicians, deciding what to do was “a political decision”. Medley told the Guardian that Johnson, Hancock and other ministers continually saying they have been guided by the scientists has “sometimes gone a bit past the mark”. Asked if he meant that the politicians were passing the buck, Medley replied: “Yes.”

Even after the stark warning that the NHS would be overwhelmed if the policy did not change, Johnson and his government still hesitated. He made another speech that day in which he advised “drastic action” was now needed, but the measures were advisory and still tentative. People over 70, pregnant women, and those with some health conditions were advised only to “avoid all unnecessary social contact”. Britons were asked “where they possibly can” to work from home, and Johnson told them “you should avoid pubs, clubs, theatres and other such social venues”, although all were permitted to stay open.

During the week after 16 March, there was a fierce debate within government about whether a stricter lockdown needed to be imposed. “Several of us thought measures needed to be introduced earlier,” one source close to the Cabinet Office said. Hancock appears to have been under great pressure, stretched between that view and resistance elsewhere to taking genuinely drastic action. A senior source at the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) recalled discussions about the herd immunity policy continuing, despite Hancock having disowned it, and a senior official still advocating it. “His basic view was that we were all going to develop antibodies, and ultimately the question was how to manage the release of the disease into the population over time.”

The DHSC source sums up this period soberly: “They knew we would have to go into lockdown; they were debating when. Every single day they wasted, every day we weren’t in lockdown, was resulting in people contracting the disease – people who have since died.”

Reflecting on the presence at Sage of Cummings and Warner, some attendees now say the group’s deliberations were affected by a sense of what could feasibly be done, with a government run by politicians to whom a lockdown looked unthinkable, although others say they were not. Then, that week, when stricter measures were needed, some say it was useful to have Cummings there, because they knew he would communicate that directly to Johnson.

One source in Downing Street who personally urged the prime minister to stop delaying and move into lockdown that week said his reticence was partly down to his “libertarian instinct”. “There was also a bit of ‘rabbit caught in headlights’.”

|

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote